According to Scrooge, it was the Age of Steam!

I began writing The Truth About Jacob Marley without much planning. But I did know a few things. For instance, I needed Jacob Marley to be alive on the Christmas Eve of 1841, exactly as Frederick Truelock states on Page 1 of the novel. I picked 1841 because Dickens’ novel came out in December of 1842. I started keeping a spreadsheet before I wrote much else and I’m glad I did. In it I listed the years, how old characters were at the time, and when the plot points occurred. My novel begins much earlier than does A Christmas Carol, but of course I drew some of the earlier parts from Stave Two, when Scrooge is visited by the Ghost of Christmas Past.

I also put a couple of markers in the spreadsheet: “Victoria becomes queen” and “V marries Albert.” Those were the only historical events I thought of initially. I hadn’t realized yet that I was writing a historical novel—if you can call it that. A Christmas Carol is certainly not one. Dickens was writing about his contemporary society at the time, and any mention of poverty or unfair laws is also contemporary. He never refers to current events in this book, as far I can tell. Most historical fiction is about major events (e.g., War and Peace) and how people were affected by them. Dickens would later do that with A Tale of Two Cities. But not here.

So I started out only worrying about what kind of guy Marley was. But I wanted my novel to be accurate of course, so I kept looking things up online. I had questions. When were those cloth machines in Manchester fully up and running? When did the railways start? When did people start taking laudanum or other drugs? Every time I felt a character might be about to do something questionable for the time period, I looked it up. After a while, I began to see that the details I put in the story were giving it a flavor and richness that I liked. I thought of it as background scenery.

Looking back on the whole process, I think a case could be made for my novel being called historical fiction after all. Why? Because my characters are sometimes influenced by certain events, or at least by certain changes in society, that were afoot. For instance, and this turned out to be a lucky discovery, the whole idea of the Christmas tree was fairly new. Sure, people were decorating by placing greenery and mistletoe in their homes, but a whole tree? The landed gentry might be doing that, but not many everyday people. I stumbled on something else. On their first Christmas together, Prince Albert surprised the Queen by secretly importing spruce trees all the way from his native home in Germany to the palace. It was in all the magazines, you know. So ordinary people started chopping down evergreen trees or buying them from street vendors.

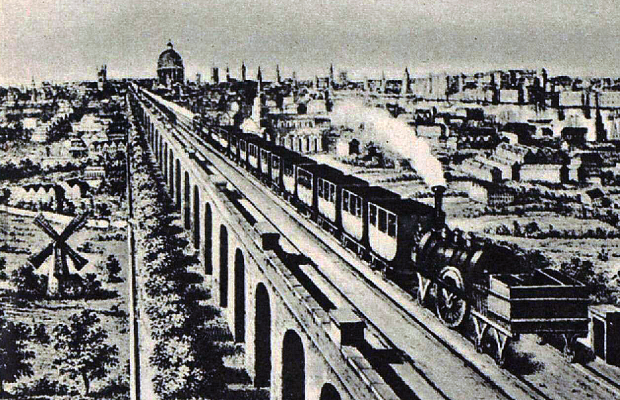

There were other lucky discoveries. When Fred’s wife goes home to visit her mother, I wondered if she might go by rail. It turns out the world’s first elevated railway was built between between a point near London Bridge to Greenwich. They built brick viaducts (see picture at top) containing more than 850 arches to elevate the rails. And Fred is very concerned about the safety of this engineering wonder. Who can blame him? So here is a small moment in history that served to influence my plot after I discovered it. That wasn’t all. When Fred decides to mail a letter to his wife, my radar went off again. How did one mail a letter in those days? It turns out that adhesive stamps were now available. They were not perforated, so you had to cut them out of a sheet. The stamp only cost a penny and with it a half-ounce letter could be sent to any place in the country. That fact had little bearing on the story, except to save Fred a trip to the post office, but it does add more color.

For me, this kind of historical fiction flows from the needs of character and plot to the historical events, not the other way round. I didn’t read about the railway and decide to put it in my story; I had a need for a railway and found one that was interesting.

But things still flow both ways, for by choosing that preposterous elevated railway, I gave Fred one more thing to worry about.

I once wrote to a friend suggesting this blurb: “In this engaging novel the events of the classic Christmas story are re-imagined and set against the panorama of the early Victorian era.” I still think that is a good description for it. “Panorama” contains the historical backdrop that I wanted and needed but had to discover as I went along.